Spillionaires: Profiteering And Mismanagement In The Wake Of The BP Oil Spill (ProPublica Special Investigation)

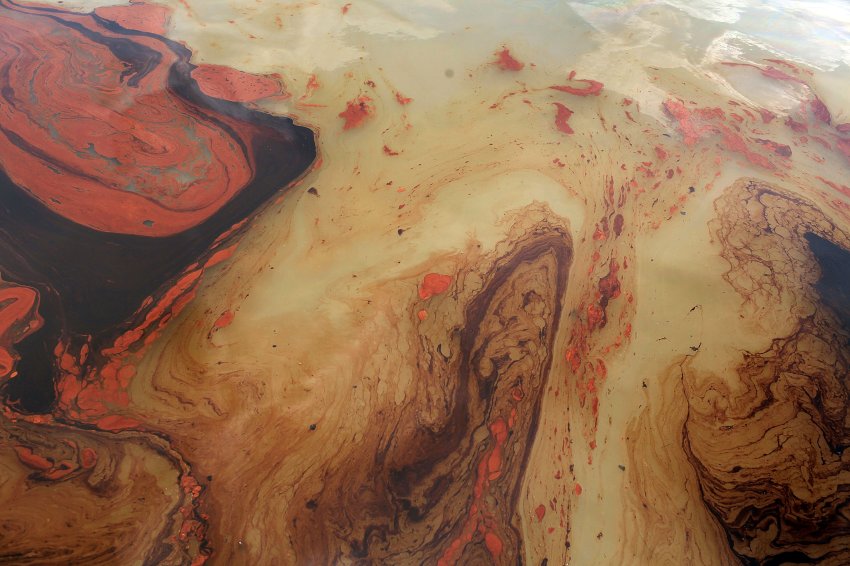

The oil spill that was once expected to bring economic ruin to the Gulf Coast appears to have delivered something entirely different: a gusher of money.

Some people profiteered from the spill by charging BP outrageous rates for cleanup. Others profited from BP claims money, handed out in arbitrary ways. So many people cashed in that they earned nicknames -- "spillionaires" or "BP rich." Meanwhile, others hurt by the spill ended up getting comparatively little.

In the end, BP's attempt to make things right -- spending more than $16 billion so far, mostly on claims of damage and cleanup -- created new divisions and even new wrongs. Because the federal government ceded control over spill cleanup spending to BP, it's impossible to know for certain what that money accomplished, or what exactly was done.

Some inequities arose from the chaos that followed the April 20 spill. But in at least one corner of Louisiana, the dramatic differences can be traced in part to local powerbrokers. To show how the money flowed, ProPublica interviewed people who worked on the spill and examined records, including some reported earlier by the New Orleans Times-Picayune, for St. Bernard Parish, a coastal community about five miles southeast of downtown New Orleans.

Documents show that local companies with ties to insiders garnered lucrative cleanup contracts and then charged BP for every imaginable expense. The prime cleanup company, which had a history of bad debts and no oil-spill experience, submitted bills with little documentation or none at all. A subcontractor charged BP $15,400 per month to rent a generator that usually cost $1,500 a month. A company owned in part by the St. Bernard Parish sheriff charged more than $1 million a month for land it had been renting for less than $1,700 a month.

Assignments for individual fishermen followed the same pattern, with insiders and supporters earning big checks.

"This parish raped BP," said Wayne Landry, the chairman of the St. Bernard Parish Council, referring to the conduct of its political leadership. "At the end of the day, it really just frustrates me. I'm an elected official. I have guilt by association."

The economic benefits that rippled through St. Bernard Parish were seen in varying degrees throughout the Gulf. In the six months after the spill, sales tax receipts, a key measure of economic activity, rose significantly in eight of the 24 most affected communities from Louisiana to Florida, despite the national recession. Only one community, in Mississippi, saw its receipts dip significantly. Local governments also profited. A recent story by the Associated Press found that governments along the coast used BP money to buy SUVs, Tasers and other equipment not necessary to clean up oil.

According to sales tax collections, Louisiana made out better than anywhere. Sales tax collections from Plaquemines Parish rose more than 71 percent, while St. Bernard saw the biggest jump of all. The parish collected almost $26.8 million in sales and lodging tax receipts in the six months after the spill, almost twice as much as over the same period in 2009. Flush with cash from cleanup and claims, many fishermen bought new toys, boats and trucks. Sales at the nearest Chevrolet dealer rose 41 percent.

Some of the influx of money can be traced to the efforts of St. Bernard's parish president, Craig Taffaro Jr., a 45-year-old psychotherapist with a wrestler's build, a cue-ball head and a trimmed goatee.

Just days into the crisis, Taffaro did what many parish presidents did: He invoked a Louisiana law that allowed him to declare a 30-day emergency and handle the crisis without most normal government checks and balances. But Taffaro used his powers more broadly than most, saying that he wanted to put money back into the community. Unlike the leaders of other Gulf communities, Taffaro -- not BP -- chose the prime contractor that supervised the cleanup. He and his allies also decided which fishermen would be hired to put out boom and search for oil. At one point, Taffaro hired his future son-in-law to work in the finance department and help on the spill.

In some ways, parish residents seemed to view the disaster and BP's culpability as a way to recover from earlier blows. More than other coastal communities, St. Bernard bore the brunt of Hurricane Katrina, which flooded almost every home in August 2005. The population dropped almost in half, from about 67,000 in 2000 to about 36,000 in 2010, largely because people didn't come back after Katrina and the hurricanes that followed. Before the spill, the parish slashed its budget by 11 percent, cutting garbage collection, the fire department and mosquito control. There was just no money.

The spill changed that. Fishermen were paid to lay out protective boom, the floating material used to corral the oil. Contractors were hired to manage the cleanup and provide security. Claims money began flowing to people who said their lives had been upended by the crisis.

The parish government was among the first to benefit, snagging a $1 million check for oil-spill expenses. Parish employees went shopping for cameras, printers, a file cabinet, staplers, six pairs of children's scissors and 712 shirts emblazoned with the parish name. Some of the money also went to overtime pay for more than 40 parish employees, including three who claimed overtime for picking up dog food for the animal shelter. St. Bernard's homeland security director, David Dysart, a salaried employee and Taffaro's good friend, was paid almost $23,000 for working 497 hours of overtime in less than seven weeks. That meant he was working an average of more than 16 hours a day, including weekends.

As the money flowed, complaints spread. Some beneficiaries didn't necessarily suffer from the spill but had social or political connections. Subcontractors said those at the top of the cleanup creamed off money for doing very little, while those at the bottom earned much less for doing the actual work.

At first, everyone was angry with BP. But as the months wore on, some St. Bernard residents directed their frustration at Taffaro, blaming him for handing out jobs and money to a small group of insiders.

Meanwhile, Taffaro was attacking BP and the federal government in the media, appearing on TV alongside Gov. Bobby Jindal and testifying in Congress. His outrage was palpable. There wasn't enough boom, coordination or respect for the local government. BP wasn't making good on its obligations.

The pressure paid off. Taffaro at one point boasted that St. Bernard had doled out more BP cleanup money to commercial fishermen than any other Louisiana parish. His claim is impossible to verify, because neither Taffaro nor anyone else would provide details about the spending numbers.

BP gave only limited information to ProPublica, and declined to comment on allegations it had been overcharged. The U.S. Coast Guard, the federal agency most involved with overseeing BP's response, said the government and BP decided cleanup priorities together.

Taffaro and other St. Bernard officials refused to respond to the public-records requests ProPublica began filing in November. When asked again last week why the parish hadn't provided any records, Dysart said he would be happy to help but that filling the request would take time and cost a lot of money.

"I'm in the process of really, truly trying to assist you," said Dysart, who is also the parish interim chief administrative officer.

In response to questions submitted by ProPublica last month, Taffaro said through his spokeswoman that he can approve overtime for salaried employees in extenuating circumstances and that Dysart eventually decided to stop taking overtime. Taffaro said there was no law against hiring his future son-in-law because he was not yet married, and that paying overtime for picking up dog food was necessary because the spill had caused fishermen to abandon their dogs.

Taffaro also said that the tax receipt bubble was "a false economy," similar to what happened after Hurricane Katrina.

Continue reading at ProPublica...

--

Supporting Documents:

List of Overtime for the Cleanup in St. Bernard Parish

Latest Stories in this Project from ProPublica:

###

BP: Still Not As Evil As Goldman Sachs (Brand Ranking)

Video Timeline Of Obama's Daily Response To BP Oil Spill (MUST SEE)

Slideshow:

Apr 14, 2011 at 4:59 PM

Apr 14, 2011 at 4:59 PM

Reader Comments (4)

http://www.zerohedge.com/article/greek-10-year-yield-surges-over-132-euro-falls-against-gold-and-particularly-silver

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-04-14/nato-struggling-to-resolve-divisions-over-libya-as-qaddafi-retains-power.html

the 2nd 1/2 of the story is better than the first...

Yale...Course...Game Theory...This course is an introduction to game theory and strategic thinking. Ideas such as dominance, backward induction, Nash equilibrium, evolutionary stability, commitment, credibility, asymmetric information, adverse selection, and signaling are discussed and applied to games played in class and to examples drawn from economics, politics, the movies, and elsewhere.

Nothing about business ethics and morals. By the way, I listened to the podcast of this course. For what it is, it is a great course.