"Nobody on this planet represents more vividly the scam of the banking industry than Bob Rubin. He made $120 million from Citibank, which was technically insolvent. And now we, the taxpayers, are paying for it."

---

Rethinking Bob Rubin From Goldman Sachs Star to Crisis Scapegoat

By William Cohan

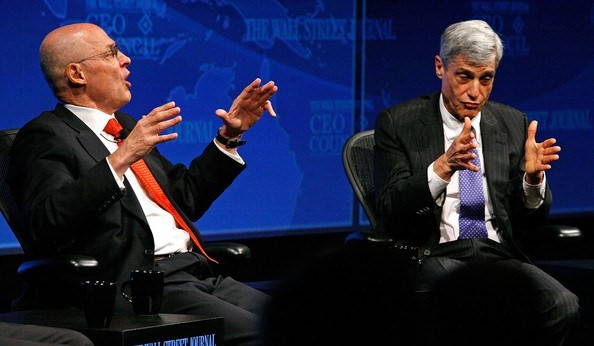

There are questions about just how wise and thoughtful Robert Rubin really is, especially on the fourth anniversary of a financial crisis in which he played a pivotal, under-examined role. Rubinomics -- his signature economic philosophy, in which the government balances the budget with a mix of tax increases and spending cuts, driving borrowing rates down -- was the blueprint for an economy that scraped the sky. When it collapsed, due in part to bank-friendly policies that Rubin advocated, he made more than $100 million while others lost everything. “You have to view people in a fair light,” says Phil Angelides, co-chair of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, who credits Rubin for much of the Clinton era prosperity. “But on the other side of the ledger are key acts, such as the deregulation of derivatives, or stopping the Commodities Futures Trading Commission from regulating derivatives, that in the end weakened our financial system and exposed us to the risk of financial disaster.”

Taxpayer Money

After he stepped away from Treasury in 1999, Rubin moved to Citigroup, and until 2009 he served as chairman of the executive committee and, briefly, chairman of the board of directors. On his watch, the federal government was forced to inject $45 billion of taxpayer money into the company and guarantee some $300 billion of illiquid assets. Taxpayers ended up with a 27 percent stake in Citigroup, which was sold in 2010 at a cumulative profit of $12 billion.

Rubin gave up a small portion of his contracted compensation--but was still paid around $126 million in cash and stock during a tenure in which his serenity has come to look a lot more like paralysis.

“Nobody on this planet represents more vividly the scam of the banking industry,” says Nassim Taleb, author of The Black Swan. “He made $120 million from Citibank, which was technically insolvent. And now we, the taxpayers, are paying for it.”

Goldman Sachs

During his 26 years at Goldman Sachs (GS), Rubin rose from trader to the corner office, and along with his partner, Stephen Friedman, helped transform Goldman from an investment bank into shorthand for financial dominance. Goldman has made thousands of people, including Rubin, very rich. But the firm’s reputation for avarice has also created a cloud that follows its all-star alumni into civic life. The case against Rubin’s performance as a public servant is mainly about that cloud. As Treasury Secretary, was he motivated by a desire to serve the people, or an opportunity to serve himself and his friends?

Riles Critics

It’s not his personality that riles critics of Rubin’s four-and-a-half-year tenure at Treasury. It’s his failure to tame the 1999 repeal of Glass-Steagall and the wild expansion of over-the-counter derivatives, which were traded between banks, out of the public eye. “The changes that Robert Rubin drove through in the 1990s certainly helped plant the seed for the collapse,” says Angelides.

Rubin’s legion of defenders stir at any mention of Glass- Steagall, the 1933 law that separated the activities of commercial and investment banks. “There is an assumption that Bob was pushing hard for the repeal,” says Michael Schlein, a former chief of staff at the Securities and Exchange Commission and a former Citigroup executive. “I was there. That’s not the way it happened.”

No Restrictions

In testimony before the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission in March 2010, Rubin conceded that he “was an advocate of rescinding Glass-Steagall.” But: “By the time we rescinded it, there were no restrictions left in it at all except for the insurance underwriting, which had no relevance to anything that has happened since then.” What Rubin meant was that commercial banks had long been able to underwrite debt and equity and advise on mergers and acquisitions, and they had been buying investment banks through much of the 1990s. Rubin told the FCIC that ditching Glass-Steagall removed the “cumbersomeness” experienced by banks already in those businesses. In other words, he argued, he pushed for the removal of a law that was a phantom.

“Of course, it would have been better if we’d had the foresight and political strength to put in place the protections that were put in place in 2010 after the financial crisis occurred,” says Larry Summers, Rubin’s friend and successor as Treasury Secretary. “But this does not relate to the repeal of Glass-Steagall. There were virtually no restrictions on the investment banking activities of the major banks after the Federal Reserve’s undertakings during the decade before Glass- Steagall was repealed.” Speaking at a CNBC forum on July 18, Rubin said simply, “It is a myth that the repeal of Glass- Steagall contributed to the financial crisis.”

Political Convenience

Summers dismisses this as revisionism, warped by hindsight and political convenience. Instead, he offers a syllogism: If permitting the combination of commercial and investment banks caused the financial crisis, why was fixing it so dependent on commercial banks buying investment banks? True enough, many companies that took advantage of Glass-Steagall’s repeal (Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America) still exist. Souvenirs from the standalone investment banks (Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch) are available on EBay.

Derivatives Regulations And Brooksley Born

In part because of its complexity, less attention has been paid to Rubin’s role in the unleashing of the over-the-counter derivatives market. In March 1998, Brooksley Born, chairman of the CFTC, wanted to release a “concept paper” that would raise a series of questions about the possible regulation of derivatives. “I was very concerned about the dark nature of these markets,” Born told the Washington Post in 2009. “I didn’t think we knew enough about them.”

Born’s plan was to have the CFTC oversee these new, often inexplicable financial products. Rubin, Summers, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, and Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman Arthur Levitt countered that Born was out of her depth. (Levitt is a board member of Bloomberg LP, which owns Bloomberg Businessweek.) They argued that the CFTC, created in the 1970s to regulate futures contracts bought by farmers, didn’t have the authority or expertise to regulate complex derivatives in a fast-expanding market. Born was no match for their firepower. They persuaded Congress to ignore her.

Fed Bailout

In his 2003 memoir, In an Uncertain World, Rubin wrote that he favored making derivatives “subject to comprehensive and higher margin limits.” He just didn’t support doing it Born’s way, which he called “strident.” But if Rubin and others had an alternative plan, they didn’t offer it up quickly enough. In September 1998 the Long Term Capital Management hedge fund melted down, thanks in part to $1.6 billion in losses on interest rate swaps. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York had to organize a $3.6 billion bailout by its major creditors to avoid infecting the rest of the market. Then-House Banking Chairman Jim Leach (R-Iowa), who opposed giving the CFTC regulatory authority, introduced Born at a hearing by saying, “You’re welcome to claim some vindication if you want.”

Even now, Summers thinks he and Rubin were right to fight Born’s power grab. “Our concerns were not with respect to the desirability of derivatives regulation,” Summers says. “Career lawyers at the Fed, the SEC, and the Treasury insisted that the CFTC’s proposed approach would raise potentially grave questions about the enforceability of existing contracts.” Born, Summers adds, didn’t know what she was attempting to regulate, making it as much of a reach to credit her with prophesizing the financial crisis as it is to hold Rubin or Summers responsible for failing to prevent it. “It should be noted,” adds Summers, “that the credit-default swaps and the collateralized-debt obligations that were central to the crisis barely existed at the end of the Clinton administration.” Born declined to comment for this story.

Judgement Errors

Greenspan, Levitt, and others have conceded errors in judgment that, upon reflection, may have created conditions that led to the crisis. Clinton, too, wishes he had a few mulligans. The president says he raised concerns about derivatives and their lack of regulation to Greenspan, though not to Rubin. “I should have aired the debate we had in private in public,” Clinton says, “and at least raised the red flag.”

Rubin hasn’t looked back, at least not publicly. Those close to him say that he dealt with the facts of the financial markets as they presented themselves and was without outside influences. If Rubin failed to focus on the future ramifications of a few key policy decisions, it might be because he was fighting global crises in the present. He was also persuading a president under constant political attack to implement Rubinomics. Having your name attached to the policy that led to the largest postwar expansion in American history is a pretty effective way to obscure other controversies. “Bob has been acclaimed as the most effective Treasury Secretary since Alexander Hamilton,” said Clinton on July 2, 1999, the day Rubin departed as Treasury Secretary. “And I believe that acclaim is well deserved.”

Continue reading at Bloomberg...