Seventy-seven years ago, with a law that took only 3½ pages of text, Congress created the Home Owners’ Loan Corp. to acquire defaulted residential mortgages from lenders and investors and then refinance them at more favorable and sustainable terms.

In exchange for the loans, lenders would receive HOLC bonds. While the bonds would earn a market rate, the rate was lower than that of the original mortgage, But since the bond took the place of what had become a non-earning asset, and one with little prospect for ever turning a profit, banks eagerly agreed to the trade.

In addition, lenders often would take a loss on the principal value of the original mortgage. This, according to Pollock, was “an essential element of the reliquification program, just as it will be in our current mortgage bust.”

The Home Owners’ Loan Act called for the directors of the government-sponsored corporation to liquidate the company when it’s “purpose had been accomplished” and pay any surplus or accumulated funds to the U.S. Treasury. In 1951, during the height of another housing boom, they did just that, closing the pages on a period of history that has long been forgotten.

Eighteen years was probably a little longer than lawmakers originally expected. But during its life, the Home Owners’ Loan Corp. made more than a million loans to refinance troubled mortgages, according to Pollock, who had spent 35 years in banking when he left the Chicago Fed in 2004. That’s about 20% of all mortgages in the country at that time.

By 1937 alone, in what the AEI scholar calls a “remarkable scale of operations,” the Home Owners’ Loan Corp. owned almost 14% of the dollar value of all the nation’s outstanding home loans.

HOLC’s investment in any mortgage was limited by law to 80% of the underlying property’s appraised value, with a maximum of $14,000. With an 80% loan-to-value ratio, then, the maximum house price that could be refinanced would be $17,500.

A mere pittance, by today’s standards. But that was in 1933 dollars. After adjusting the $17,500 ceiling by the Consumer Price Index, the maximum today would be about $270,000, Pollock said. And based on changes in the Census Bureau’s median house price since 1940, the limit would be something on the order of $1 million.

Therefore, Pollock contends in his paper, a modern HOLC could very well operate all over the country, even in high-cost markets like California and New England.

The 1933 law also set an interest rate ceiling of 5% on the new loans HOLC could make to refinance the old ones it acquired. The spread between this rate and the cost of the bonds the HOLC Corp. issued averaged about 2.5%, according to Pollock. And with long-term Treasury rates now at about 4%, an equivalent spread would lead to a loan rate of about 6.5%.

That may be a tad higher than some borrowers would like. But at least it would be a fixed rate, never to change over the loan’s life.

According to Pollock, HOLC tried to accommodate as many borrowers as possible. But there were some borrowers that could not be rescued, no matter what. Eventually, it foreclosed on about 200,000, or 20%, of its loans. In other words, for every four borrowers who were saved, another family lost its home.

An acceptable outcome? Maybe, maybe not. But since each and every home owner who refinanced through this program started in default and was close to foreclosure anyway, Pollock, for one, says the result was “quite respectable.”

“We don’t need something of the same scale” this time around, Pollock said of the HOLC, which had as many as 20,000 employees. “But I think the concept offers a pretty intriguing historical perspective. What I especially like about it is that it set up to do a job, and when it was done, it closed down.”

Continue reading...

##

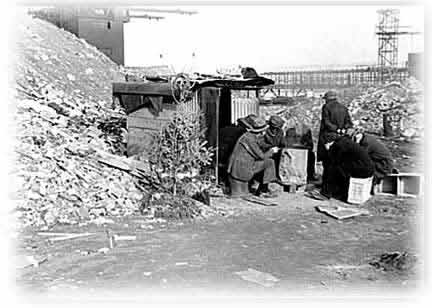

About Hoovervilles - Wikipedia